Dr. Bunchar Pongpanich of Thailand is unearthing new information about the history of his country, a history chronicled on the beads he collects.

According to the

Bangkok Post, Dr. Bunchar’s interest in beads began when a villager brought him an inscribed pendant he found in the southern part of Thailand, a region called Suvarnabhumi.

“The engraved script on the pendant was made in a dialect called Brahmin that was used from the reign of King Ashoka [c 265 to 238 BC] up to the 5th century of the Buddhist Era [1st to 2nd century BC],” said Dr. Bunchar. “We know that Buddhism arrived in the region at that time, but archaeological evidence that has been found in the country dates back only to the 9th century. But this bead dates farther back, to the 5th century.”

Other beads in Dr. Bunchar’s collection reveal that Suvarnabhumi may have been a major bead production center, rather than just a bead trading station, which was the theory prior to these finds. Furthermore, Dr. Bunchar has acquired beads from other civilizations, including a coin that may prove the early arrival of Islam in Suvarnabhumi.

How amazing that such tiny artifacts can tell the story of an entire country and beyond! And how fitting that Dr. Bunchar’s beads are now on display in an exhibit called “Beads and Beyond” at Thailand’s

National Discovery Museum. It makes me wonder - what story will our beads tell if they find their way into a museum some day?

Map from

www.visit-thailand.info.

BEADS AND BEYOND

An exhibition sheds new light on the ancient trading hub of Suvarnabhumi

Trained professionally as a doctor, better known as a teacher, a social activist and a devout Buddhist, now Dr Bunchar Pongpanich makes his name as a bead collector - a serious one.

DIGGING DEEP: Dr Bunchar examines a bead found at an excavation site in Phangnga province.

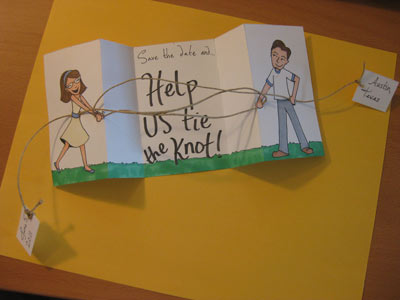

Ancient beads from his private collection are now on display at "Beads and Beyond" at the National Discovery Museum.

The exhibition has wowed archaeologists and enthusiasts since its opening in December due to the diversity of the beads' origins and the periods in which they were made, which give significant clues about the history of the southern part of Thailand - a trading hub of the area known as Suvarnabhumi.

While Dr Bunchar, now 52 and secretary of the Suthee-Rattana Foundation in Nakhon Si Thammarat, insisted he was a meticulous planner, particularly when it came to his work and future, bead collecting was something that simply happened out of the blue.

"But there are plenty of reasons to explain this 'hobby'," he said.

During a recent press tour to the bead exhibition, Dr Bunchar passionately described the exhibited items, which he said belonged to the Suthee-Rattana Foundation. He stopped at a glass panel displaying a tiny, sand-coloured pendant with ancient Indian inscriptions, saying it was this very piece that triggered his interest in ancient beads some four years ago.

"This was my inspiration to explore bead affairs," he said.

Dr Bunchar said he was directing a tsunami relief operation in Krabi's Khlong Thom district when a villager came across the tiny object and handed it to him for examination.

"The engraved script on the pendant was made in a dialect called Brahmin that was used from the reign of King Ashoka [c 265 to 238 BC] up to the 5th century of the Buddhist Era [1st to 2nd century BC]," said Dr Bunchar.

Even though the meaning of the script remains a mystery, he said, it is potential evidence to mark the arrival of Buddhism in this region at that period.

"That may tell something about Suvarnabhumi. We know that Buddhism arrived in the region at that time but archaeological evidence that has been found in the country dates back only to the 9th century. But this bead dates farther back, to the 5th century."

He also found several other ancient signs used by Buddhists before the creation of Buddha images, including a tiny bead called Tri Rattana.

HISTORY: Beads of various origins and periods at the exhibition. They were loaned by Dr Bunchar Pongpanich of the Suthee-Rattana Foundation.

The bead, despite its importance, remains largely unknown to Buddhists, he said.

"Due to its peculiar, shoulder-like design, some villagers call it a 'doll bead'. I called it a 'frog bead' which did not make any sense," he said.

It was not until he met a French archaeologist who studied beads in Khao Sam Kaeo in Chumphon in 2007, that he realised that the bead, which is made of several kinds of stones including rock crystal and carnelian, signified the Three Gems of Buddhist beliefs.

"People don't recognise it largely because they look at it upside down. The round design at the bottom is a lotus, which is dhamma, the middle part is dharmachakra, the wheel of law, and the flame at the top is the spread of Buddhism."

Dr Bunchar said he then returned to the Suan Mokkh sanctuary and went through a note written by Phra Buddhadasa during his trip to India in 1955. "His note showed that the revered monk had seen this type of bead in that country and already knew of its meanings. I noticed also that the Tri Rattana sign is a motif of some of the walls of Suan Mokkh buildings."

His collection goes beyond Buddhism-related beads, as he has acquired rare beads and coins from Greek, Roman and other civilisations including the so-called Sun-God bead.

One silver coin demonstrated the arrival of early Islam in this region, he noted.

Dr Bunchar said the finds, including remnants of stones, indicated that this area was a major bead production site, not just a bead trading station as earlier believed.

He conceded that the hobby has drawn some harsh criticism as the beads are, according to law, archaeological objects that must be surrendered to the state.

"The fact is the Fine Arts Department has no ability to protect these items from looters and smugglers. I started to collect some four years ago and still acquired rare, valuable items. Imagine what we have lost to foreign markets given that this business began more than 30 years ago," he said.

The Fine Arts Department had received heaps of beads from local villagers but hardly treasured them. There was no study or research done on the items, which are mostly piled up in museums or storerooms, he said.

His ultimate aim, Dr Bunchar said, was to ensure that these beads were preserved within Thailand.

"The items are for study and research. They allow us to know better of our nation and our history. There will eventually be a museum for these items."

More importantly, Dr Bunchar noted that he never purchased beads from middlemen.

"All were received directly from villagers who dug them up. Since they agreed to pass the items on to me, I had to take care of them in the proper way," he said, carefully avoiding the term "buy" or "purchase".

During the press tour, questions did occasionally came up about the sum of money he paid for particular items, but he gently refused to disclose them, except once, for an ancient gold Roman coin, carrying the name "Antonius".

A villager who found it wanted 300,000 baht, as a number of antique dealers had asked to see it, he said.

"I told him it was beyond my ability to keep it within the country. All I asked was to take a picture of it, ready to accept the fact that we have to lose it to foreign markets. Later on, the villager came back, agreeing to accept my 80,000 baht offer."

Dr Bunchar carefully studied and researched each item he acquired, making notes and observations.

How does he know that the beads are genuine and not reproductions?

"I took into consideration where and from whom the beads came as well as other circumstances. Basically, I know the villagers who find them; as I said there are no middlemen involved in the process. When one dug up a bead or beads, fellow villagers also knew and I could check and double-check."

When asked if he has been approached by any bead dealers, he said: "No. Some may show an interest but never make a real offer. They know I won't sell any of them," he said in a determined voice.

Dr Bunchar said he spends a lot of time on beads, and the rest is divided between the construction of the Buddhadasa memorial site and advisory positions in state and public agencies, including the Thai Health Foundation.

What about his family - do they understand? He chuckled out loud before saying: "I'm not married ... yet I make sure that I'm at home at least one day a week to take care of Mum and Auntie, and some family business in Nakhon Si Thammarat that includes a bookshop. I would say they are understanding. They were not so at first, but eventually have learned to be."

thank you